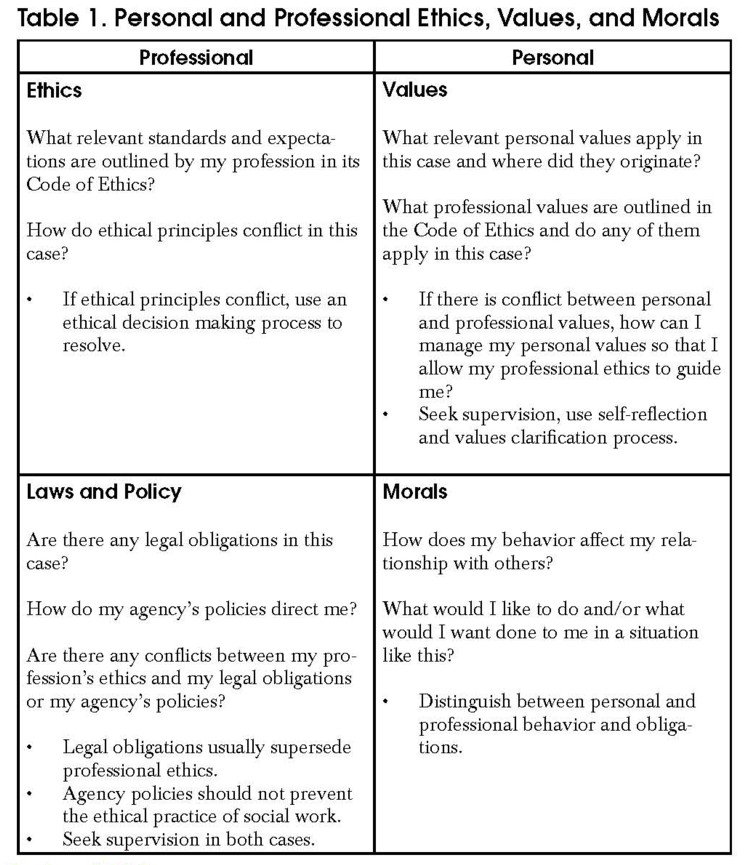

Ethical Dilemma Table 1

By: Karen Allen, Ph.D., LMSW

Social workers are routinely confronted with ethical dilemmas in practice, and social work programs infuse their courses with professional ethics and values to help students prepare for this eventuality. The Council on Social Work Education (2008) requires that students learn how to “apply social work ethical principles to guide practice, engage in ethical decision making, recognize and manage personal values in a way that allows professional values to guide practice, and tolerate ambiguity in resolving ethical conflicts” (EPAS 2.1.2).

Social work students become familiar with the Code of Ethics, learn one of the various models on ethical decision making (Congress, 1999; Dolgoff, Loewenberg, & Harrington, 2009; Reamer, 1995) and, at some point in their education, are typically required to write a paper on an ethical dilemma. However, students are not routinely taught how to recognize what an ethical dilemma is. Correctly identifying an ethical dilemma is the first step in resolving it.

What Is an Ethical Dilemma?

There are three conditions that must be present for a situation to be considered an ethical dilemma. The first condition occurs in situations when an individual, called the “agent,” must make a decision about which course of action is best. Situations that are uncomfortable but that don’t require a choice, are not ethical dilemmas. For example, students in their internships are required to be under the supervision of an appropriately credentialed social work field instructor. Therefore, because there is no choice in the matter, there is no ethical violation or breach of confidentiality when a student discusses a case with the supervisor. The second condition for ethical dilemma is that there must be different courses of action to choose from. Third, in an ethical dilemma, no matter what course of action is taken, some ethical principle is compromised. In other words, there is no perfect solution.

In determining what constitutes an ethical dilemma, it is necessary to make a distinction between ethics, values, morals, and laws and policies. Ethics are prepositional statements (standards) that are used by members of a profession or group to determine what the right course of action in a situation is. Ethics rely on logical and rational criteria to reach a decision, an essentially cognitive process (Congress, 1999; Dolgoff, Loewenberg, & Harrington, 2009; Reamer, 1995; Robison & Reeser, 2002). Values, on the other hand, describe ideas that we value or prize. To value something means that we hold it dear and feel it has worth to us. As such, there is often a feeling or affective component associated with values (Allen & Friedman, 2010). Often, values are ideas that we aspire to achieve, like equality and social justice. Morals describe a behavioral code of conduct to which an individual ascribes. They are used to negotiate, support, and strengthen our relationships with others (Dolgoff, Loewenberg, & Harrington, 2009).

Finally, laws and agency policies are often involved in complex cases, and social workers are often legally obligated to take a particular course of action. Standard 1.07j of the Code of Ethics (NASW, 1996) recognizes that legal obligations may require social workers to share confidential information (such as in cases of reporting child abuse) but requires that we protect confidentiality to the “extent permitted by law.” Although our profession ultimately recognizes the rule of law, we are also obligated to work to change unfair and discriminatory laws. There is considerably less recognition of the supremacy of agency policy in the Code, and Ethical Standard 3.09d states that we must not allow agency policies to interfere with our ethical practice of social work.

It is also essential that the distinction be made between personal and professional ethics and values (Congress, 1999; Wilshere, 1997). Conflicts between personal and professional values should not be considered ethical dilemmas for a number of reasons. Because values involve feelings and are personal, the rational process used for resolving ethical dilemmas cannot be applied to values conflicts. Further, when an individual elects to become a member of a profession, he or she is agreeing to comply with the standards of the profession, including its Code of Ethics and values. Recent court cases have supported a profession’s right to expect its members to adhere to professional values and ethics. (See, for example, the Jennifer Keeton case at Augusta State University and the Julea Ward case at Eastern Michigan University.) The Council on Social Work Education states that students should “recognize and manage personal values in a way that allows professional values to guide practice” (EPAS 1.1). Therefore, although they can be difficult and uncomfortable, conflicts involving personal values should not be considered ethical dilemmas.

Two Types of Dilemmas

An “absolute” or “pure” ethical dilemma only occurs when two (or more) ethical standards apply to a situation but are in conflict with each other. For example, a social worker in a rural community with limited mental health care services is consulted on a client with agoraphobia, an anxiety disorder involving a fear of open and public spaces. Although this problem is outside of the clinician’s general competence, the limited options for treatment, coupled with the client`s discomfort in being too far from home, would likely mean the client might not receive any services if the clinician declined on the basis of a lack of competence (Ethical Standard 1.04). Denying to see the patient then would be potentially in conflict with our commitment to promote the well-being of clients (Ethical Standard 1.01). This is a pure ethical dilemma because two ethical standards conflict. It can be resolved by looking at Ethical Standard 4.01, which states that social workers should only accept employment (or in this case, a client) on the basis of existing competence or with “the intention to acquire the necessary competence.” The social worker can accept the case, discussing the present limits of her expertise with the client and following through on her obligation to seek training or supervision in this area.

However, there are some complicated situations that require a decision but may also involve conflicts between values, laws, and policies. Although these are not absolute ethical dilemmas, we can think of them as “approximate” dilemmas. For example, an approximate dilemma occurs when a social worker is legally obligated to make a report of child or domestic abuse and has concerns about the releasing of information. The social worker may experience tension between the legal requirement to report and the desire to respect confidentiality. However, because the NASW Code of Ethics acknowledges our obligation to follow legal requirements and to intervene to protect the vulnerable, technically, there is no absolute ethical dilemma present. However, the social worker experiences this as a dilemma of some kind and needs to reach some kind of resolution. Breaking the situation down and identifying the ethics, morals, values, legal issues, and policies involved as well as distinguishing between personal and professional dimensions can help with the decision-making process in approximate dilemmas. Table 1 (at beginning of this article) is an illustration of how these factors might be considered.

Conclusion

When writing an ethical dilemma paper or when attempting to resolve an ethical dilemma in practice, social workers should determine if it is an absolute or approximate dilemma; distinguish between personal and professional dimensions; and identify the ethical, moral, legal, and values considerations in the situation. After conducting this preliminary analysis, an ethical decision-making model can then be appropriately applied.

References

Allen, K. N., & Friedman, B. (2010). Affective learning: A taxonomy for teaching social work values. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 7 (2). Retrieved from http://www.socialworker.com/jswve.

Council on Social Work Education. (2008). Education policy and accreditation standards (EPAS). Retrieved from http://www.cswe.org/NR/rdonlyres/2A 81732E-1776-4175-AC42-65974E96BE66/0/2008EducationalPolicyandAccreditationStandards.pdf.

Dolgoff, R., Lowenberg, F. M., & Harrington, D. (2009). Ethical decisions for social work practice (8th Ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Congress, E. P. (1999). Social work values and ethics: Identifying and resolving professional dilemmas. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Group/Thompson Learning.

National Association of Social Workers. (1996, revised 1999). Code of Ethics of the National Association of Social Workers. Washington, DC: Author.

Reamer, F. (1995). Social work values and ethics. New York: Columbia University Press.

Robison, W., & Reeser, L. C. (2002). Ethical decision making for social workers. New York: Allyn & Bacon.

Wilshere, P. J. (1997). Personal values: professional questions. The New Social Worker, 4 (1), 13.

Karen Allen, Ph.D., LMSW, is an associate professor at Oakland University’s Social Work Program.

This article appeared in THE NEW SOCIAL WORKER, Spring 2012, Vol. 19, No. 2. All rights reserved. Please contact the publisher/editor for permission to reprint/reproduce.

Related articles: